Evangelion (Neon Genesis Evangelion)

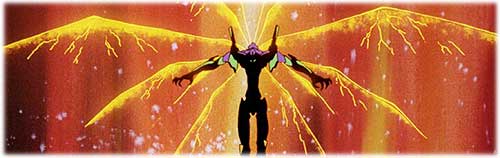

Multi-layered and thought-provoking, Neon Genesis Evangelion

is without a doubt the most influential and most popular mecha

series to come out in the nineties. Deserving of its reputation

as a complex work, this series has spawned more heated intellectual

discussions (live and on internet messageboards) than any other.

Its introspective nature and its privileging (especially in

the latter half of the series) of Freudian and Jungian psychology,

along with its heavy use of Judeo-Christian and Darwinian metaphor,

are what make Evangelion more than just another mecha

show.

|

|

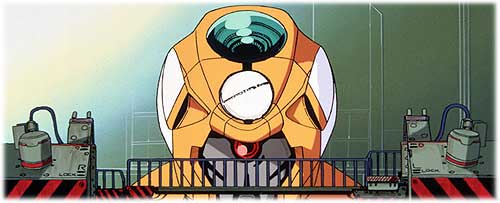

| The post-apocalyptic series begins with 14-year-old Shinji

Ikari (right) being called to the secret underground NERV headquarters

and being told by his father that he must pilot Evangelion Unit

01, a giant (and frightening) mecha, and use it to fight the

attacking Angels. In a move deliberately contrary to the traditional

mecha formula, director Hideaki Anno creates in Shinji a true

anti-hero--depressive, brooding, and at times disturbingly passive--which

is shown up front when Shinji tells his father that he doesn't

wish to pilot Unit 01. |

|

|

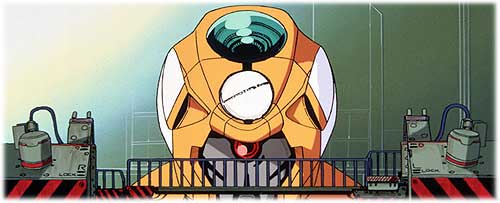

Ultimately, Shinji decides to take on the awesome responsibility

of piloting the Evangelion. At this point Anno could have let

Evangelion sink into a more traditional, action- and

male-oriented rut, and on the surface, the first half of the

series does appear to follow the monster-of-the week

formula: out of nowhere an Angel appears, Shinji and others

fight the Angels in their Evangelions, the Angel is defeated,

the credits roll. But Anno has deeper intentions.

|

|

Not only do these early episodes lull the viewer into a false

sense of security (which will then be torn apart later in the

series), but they contain a sophisticated and subtle treatment

of some of the series' themes: most notably, disfunctional sexual

and familial relationships as well as the problematic role of

science in the modern world. |

Anno really gets going in the second half of the series, taking

the audience down considerably darker, more twisted roads...

so dark, in fact, that after the airing of episode 18, the Japanese

PTA complained about the series' growing use of disturbing violence.

But there is more to the series than shock value, and the latter

half delves even deeper into the themes subtly set up at the

start. The Judeo-Christian themes in particular become impossible

to ignore: cross-shaped explosions, monstrous attackers with

Jewish names, Stars of David, the Tree of Sephiroth, and explicit

references to the Dead Sea Scrolls all appear in greater frequency

as the series builds up to its controversial ending(s).

|

|

The TV ending

Due to budget and time limitations, Anno was forced to rewrite

his original ending for Evangelion, and what then appeared

on television as episodes 25 and 26 caused quite the controversy.

Taking place largely in Shinji's head, these episodes are

a fascinating and thought-provoking conclusion to the series.

While they tie up the show's psychological (Freudian) themes

exceptionally well, they fail to deal with the show's religious

themes, much less resolve the plot of the series.

|

|

|

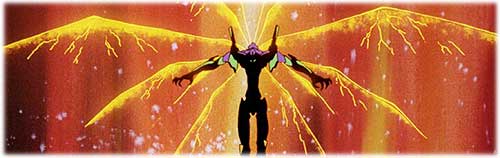

The movie ending

After being surprised and confused by the TV ending, Japanese

fans demanded a remake of the ending. GAINAX (the company

that made the series) raised the funds, and the movies Death

& Rebirth and The End of Evangelion were the

result. The End of Evangelion in particular gives the

series a true sense of completion, as it focuses more on external,

literal events than does the "internal" TV ending.

|

|

Verdict

Truly a masterpiece, Hideaki Anno's Neon Genesis Evangelion

is a must-see for any anime fan wishing for something deeper

and more thought-provoking than a mindless action series.

|

All images used on this page are copyright GAINAX

Co., Ltd., and are used with permission.

|